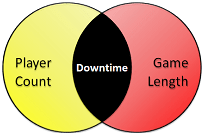

This week’s dimension of gaming is Downtime. We’ll define downtime simply as the portion of the game for which you’re not actively playing. Downtime can happen during other players’ turns, during setup or cleanup, or during intermediate steps of a game like dealing cards for a new round. This dimension of gaming exists at the intersection of Game Length and Player Count: longer games increase the risk of downtime because as the length of a game increases, the length of time a given player is not doing anything increases. And as games are scaled up to include more players, designers need to keep in mind not only how the mechanics balance but also how adding more players affects the player experience, especially as it relates to taking a longer time before any individual player gets to take his next action.

This week’s dimension of gaming is Downtime. We’ll define downtime simply as the portion of the game for which you’re not actively playing. Downtime can happen during other players’ turns, during setup or cleanup, or during intermediate steps of a game like dealing cards for a new round. This dimension of gaming exists at the intersection of Game Length and Player Count: longer games increase the risk of downtime because as the length of a game increases, the length of time a given player is not doing anything increases. And as games are scaled up to include more players, designers need to keep in mind not only how the mechanics balance but also how adding more players affects the player experience, especially as it relates to taking a longer time before any individual player gets to take his next action.

Downtime is a great opportunity to discuss the paradox of choice, which plays out in the context of game design as analysis paralysis.

The Paradox of Choice

When presented with multiple options, game theory suggests that a person, as a rational actor, will make the optimal choice. Given the choice between a hot dog and a hamburger at a cookout, a person who really loves hamburgers will pick the hamburger almost every time. With more options, it seems reasonable that a decision-maker could be even happier: suppose someone else at the cookout leaned slightly toward the hot dog camp but wasn’t crazy about either option. The addition of grilled chicken as a third choice would allow that person to optimize the decision he had to make.

This month we’re excited to bring you an interview with a game designer that has stood out to us for his work with interesting themes. Vital Lacerda has emerged in recent years as a designer of heavy Eurogames with the published success of both

This month we’re excited to bring you an interview with a game designer that has stood out to us for his work with interesting themes. Vital Lacerda has emerged in recent years as a designer of heavy Eurogames with the published success of both